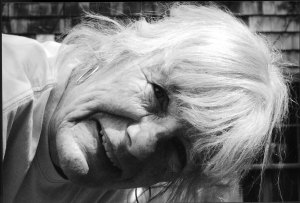

Pete Baker and her Gardens

(Memorial Service, Friends Meeting House, Westport Massachusetts. July 28, 2012)

Many of you knew Pete when she made her first vegetable garden at 670 Drift Road. I didn’t know her then, but Geraldine says: the previous owner had graveled the space, so that Pete had to start by making her own dirt––She taught herself about composting, organic gardening, and then she did it… At 29 Drift Road, Pete’s gardening went into overdrive. It was all she wanted to do. She resented all other interruptions (winter, visitors) that kept her from it.

I first met Pete in the early 1990s when she came over to the church we had recently moved into to see if she wanted the de-consecrated outhouse in our back yard. It was listing and dilapidated; of course she wanted it. Outbuildings of any kind, small and large, were an important part of her gardens. The fact that she wanted this, of course, made it seem suddenly desirable to me, and thus impossible to part with. So we kept the outhouse, and invited her to dinner.

When I told Pete I wanted to redesign the garden at the church, she took me in hand and taught me many things, among them the virtues of well-composted cow manure. (I was so impressed with her view of manure that I ordered a truckload of it to be delivered on my fiftieth birthday). While gardening, she taught me that nothing is fixed or frozen into place––every boulder, no matter how large, can be pried up with a long enough crow bar—and also every boundary can be transcended. When she saw the plans I had drawn up, she said, “Oh no! You have to leave enough of a grassy space in the middle for a couple to lie down and…couple!”

Pete was immensely generous with her time, and we went collecting in her sky blue truck to Sylvan’s and Haskell’s and Peckham’s and Avant Gardens. She taught by instruction, showing me how to free up potbound roots before planting, how deep to dig, when to give something a good whack––but she also taught by example: each of her gardens: from the small entrance terrace with the old bricks tracing the path around the circle of vinca with the pink rose; to the lacy mauve meadow rue along the walk by the house, to the grapes climbing up the arbor by the deck, or the crimson poppies in front of the greenhouse––each had a different mood, produced a different joy.

Outbuildings were part of the gardens, and so, too were stone walls. She cleared the stream and its stone channels so that the watercress would flourish. Further into the woods, she created the ponds, with their rushes and grasses and cardinal flowers. And deeper in the forest always she had woods-clearing and path-grooming projects. Sometimes Turk’s Cap lilies would appear where she had cleared the understorey. Again, boundaries didn’t stop her, and she was always game for a trespass into neighboring land. The whole territory was part of her canvas for bringing forth beauty.

A glorious example of Pete’s trespassing of boundaries, and also definitions was her award-winning exhibit at the New England Flower Show in 1992. It was, of course, A Cellar Hole. Her love of old buildings and history always led her to take pleasure in linking then and now. (She would often puzzle us by giving us directions to “Turn left at the old mill,” meaning “Turn left at the place where the mill once was, but now you see only undifferentiated forest.”)

She later described the effect of the Flower Show exhibit in her book, Collecting Houses:

The ruins were too far gone to know what the farmhouse had looked like. All that remained was a section of chimney, the fireplace hearth, and a stone-lined foundation.

At first, she writes, she had been totally dismayed by the Boston Expo Center, with its cement floor, black cloth backdrop, fluorescent lights, and ceiling of corrugated metal. But then she and her colleagues put the stones in place, and “By the end of the day, the dark and light shapes of the stones had become linked together like an architectural amulet. Delighted, I poked tiny plants of violets and ferns in between the stones, then spread the artifacts in the cellar hole––pieces of blue and white earthenware, a ceramic jug, charred pieces of wood, broken bottles, a rusted axe, the sole of a shoe, animal bones, old quahog shells––things that defined a long-ago time.”

For Pete, such things were the core of narrative. She could construct any number of stories from them.

I went to that flower show and when I came to her startling construction, I didn’t think it was an exhibit. It felt as though it had been there forever, and the whole Boston Expo Center had grown up around it. It was a ruin, half covered with autumn leaves, bits of an old garden still persisting:vinca, laurel, and white lilac; columbine and wild geranium. It felt as though you weren’t supposed to be there––as though in order to have stumbled on this old cellar hole in the woods, you would have committed a trespass. And yet, it felt like the right thing to do. It was a necessary trespass.

Like every one of Pete’s gardens, it was a world, hidden and public and still strangely intimate. Deep and beautiful and full of the mysteries.