Museum of Russian Icons

A few days ago a huge statue of Juno descended through a skylight at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. The curator of Greek and Roman Art commented,

“As in ancient Rome, MFA visitors will be awestruck by the physical presence of the gods and the power of the empire…We are delighted to welcome Juno to the MFA….”

We often refer to statues and paintings of gods as though they were deities rather than representations. There is a complexity to the connection between secular and sacred in museums. I’d like to try to get at this complexity here.

Some Questions:

Why look at the art of a religion that is not one’s own? In many museums, particularly the grand old ones, we are continually looking at the gods of others–unless we are the most profligate of pantheists. Does our gaze change, depending on whether we are thinking:

– This is from a sacred narrative I believe in

– This is from a sacred narrative I don’t believe in.

What happens to the gods when we bring them into the gallery? Do they become deconsecrated in secular space? Or do they exert some transformative power on the space that houses them, even if they are not our gods?

These questions struck me recently when I was visiting the miraculous new Museum of Russian Icons in Clinton, Massachusetts. This place is a gem–small, multifaceted, shimmering. Started in 2006, by Gordon Lankton, a local businessman, it is now a world class museum, housing his personal collection of around a thousand icons. It is full of strange and beautiful things.

Museum of Russian Icons

For example, how does one show that which is not representable. What I mean is, if a god has no physical attributes, what can one show? How can one evoke divine presence? Of course these questions are related to the work of writers, poets, mystics: How does one speak of the ineffable? Or know the unknowable?It is from my position as an outsider that I look at these images. I am not Russian; I don’t belong to this or any orthdoxy. My views would be heretical if I did, but as it is no one can excommunicate me. The fascination of these paintings transcends my own exclusion; new questions keep springing up.

Entering into this museum, suddenly surrounded by images, I have to ask, What are these icons? Why do they look like that?

Museum of Russian Icons

Icons.

Icons are representations of the sacred. Although in the Judeo-Christian tradition it is forbidden to look at god and making graven images can be problematic, in Eastern Orthodox Christianity (Greek Orthodox and Russian Orthodox and related churches), icons evoke the invisible god by showing his messengers, prophets and angels, saints and and miracles. In the case of Christ, his human aspect may be portrayed. (Though at certain times in history this, too, was mortally dangerous.) While occasionally the Ancient of Days occurs as an old man in icons, it is unclear if he is meant to be God or an eternal form of Christ.

Sometimes an icon depicts a sacred place, or scriptural narrative, or the painter’s own mystical vision or dream encounter.

Museum of Russian Icons

In this, and many other icons of Saint George, the dragon–like some dark shadow of the saint’s white steed–occupies a strange sort of space both beside and beneath the horse.

Museum of Russian Icons.

Icons showing only the head of Christ often have the startling title “Not made by Hands.” The prototype for this image is said to come from the image of Christ’s face on a towel he used after his ablutions.

The Greeks.

Why do Russian icons look like that? Where did this style of painting come from?

The simple answer is that the Russian painters were schooled by Byzantine Greeks, among them Theophanes the Greek, a Cretan trained in Constantinople, who moved to Russia in 1370. He was said to be a philosopher; his style is personal and expressionistic, as in his well known “Transfiguration” showing Christ on the mountain top, with Elijah and Moses beside him, witnessed by his disciples, Peter, John, and James, who appear stunned, bowled over. (Matthew, 17:2)

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Courtesy Wikipedia.

But saying that the Greek painters taught the Russians just pushes back the question to how did the Greeks go from Zeus/Poseidon:

National Museum of Athens. Courtesy Wikipedia.

to Christ Pantocrator:

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai.

Courtesy Wikipedia

Fayum.

Antikensammlung, Munich

Courtesy Wikipedia

The origins of Greek icons lie in Egypt – more precisely in the burial portraits of Greeks living in the Fayum region of Roman Egypt in first three centuries AD. These portraits, called the Fayum portraits, were painted from life, on wood or on linen. After death, the portraits were placed over the mummy of the subject, usually wrapped into place with linen bands. Often fully frontal or three-quarters view, they are brilliantly individual, and startlingly lifelike. We could pick each one out of a crowd of Egyptian Greeks, then or now. They look as though they have just spoken and are now listening, as though they are about to break their silence or stillness.

c.161-192 AD. Courtesy of the

Trustees of the British Museum

From mainland Greece only a handful of ancient paintings on wood panels survive. But in Egypt, because of the dry climate and with the adoption of local religious burial practices by these transplanted Greeks, around a thousand of Fayum portraits have been unearthed. They are now displayed in collections around the world. They have been brilliantly gathered and discussed in Euphrosyne Doxiadis’s The Mysterious Fayum Portraits.

Louvre, Paris. Courtesy of Wikipedia

Photo: P. Frankenstein / H. Zwietasch; Landesmuseum Württemberg, Stuttgart

“Eirene” is possibly the most beautiful of the Fayum portraits. The late Egyptian Demotic inscription across her neck reads:

Eirene, daughter of S–, May her soul rise before Osiris-Sokar, the great God, Lord of Abydos, forever.

The Techniques of the Fayum Portraits.

Two different techniques are used in the Fayum portraits: egg tempera, in which pigments are mixed with egg yolk; and encaustic, in which pigments are mixed with hot beeswax. Since beeswax does not mix with water, encaustic is impervious to moisture, and it doesn’t seem to darken or degrade with age. The encaustic portraits are vibrant and arresting, even after two millennia. All the Fayum portraits I show here are encaustic. Tempera, which was used much less often for burial portraits, is less stable as the proteins in egg yolk are water soluble.

Icon painters also use both techniques but egg tempera is by far their favorite. It can be worked more delicately, with finer brushes and greater variety of strokes. All but one of the icons I show here are done in tempera.

Beginnings of Christian Art.

In the Judaic tradition the first icon maker is the god of Genesis:

So God created man in his own image, in the image of God

created he him; male and female created he them.

The beginnings of Christian art are less well known but a good place to start is at the Onassis Cultural Center with the exhibition,”TRANSITION TO CHRISTIANITY: Art of late Antiquity, 3rd-7th C AD.” Slobodan Curcic, writing in the catalogue of this show, explains the vehement and torturous arguments which shaped the early Christian view of art. He describes how Clement of Alexandria expanded the notion of god’s image-making into a layered hierarchy:

The first level of image that god makes is the invisible Logos.

The next level of image, invisible and visible, is Christ.

The next level, imprinted by the visible image of Christ, is Humans.

Finally, farthest from god and from truth, are images made by Humans.

According to Curcic, the Late Antique theologian Pseudo-Dionysios the Areopagite’s work is also crucial. For him the icon is the will of god, and divine light dwells within images. Pseudo-Dionysios claims that the preeminent role of a symbol is to simultaneously reveal and conceal.

This is marvelous to me. I do not know what it means, but that does not make it less marvelous. What is being revealed by a symbol, and what concealed? If we knew what was being concealed, would it still be hidden? To whom? Why? It is also wonderful that we do not know exactly who Pseudo-Dionysios was. As though he, too, were concealed. We only know that he was NOT Dionysios the Areopagite.

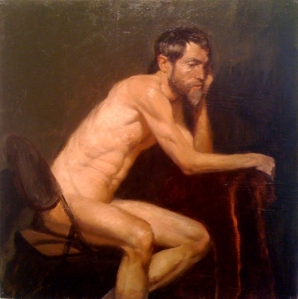

While Ancient Greeks and Romans could imagine and represent their gods with thrilling physicality, this new Christian god cannot be seen or shown. How devastating to be faced with a god who is not only invisible but unshowable. No wonder that the small household gods of the Greeks and Romans continued to exist, in the form of domestic figurines–the diminutive implying that they are of no concern, and should be allowed to slip under the radar of the graven-image injunction.

Pavel Florensky.

Pavel Florensky (left) with Sergei Bulgakov.

Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow. Courtesy Wikipedia.

The most ardent and eloquent and difficult writing on Russian icons that I have come across is Pavel Florensky’s Iconostasis. Florensky (1882-1937) was a Russian Orthodox priest, theologian, philosopher, mathematician, and scientist, who wrote extensively on Art History. Whenever I talk here of religious views of icons, it is Florensky I am attempting to understand and present, for he seems to be the grand source, although some forget to cite him.

Abstract Anatomy, Distorted Space.

Museum of Russian Icons

By the time of the Renaissance, there is a dramatic split between the Eastern, Byzantine aesthetics and those of the West. The holy figures in Russian icons become increasingly abstract, their anatomy symbolic and expressionistic, as in this painting of an emaciated John the Baptist. And the same John had his raiment of camel’s hair, and a leathern girdle about his loins; and his meat was locusts and wild honey.(Matthew 3:4)

The space surrounding the figures in icons is also abstract, structured in flat blocks of color or full of strange distortions. Mountains occur as crystalline crags; buildings become two-dimensional and often spatially impossible.

It’s not that the icon painters don’t understand our rules of perspective, but rather that for them sacred space obeys its own symbolic rules; it cannot be confined to the proportion and scale of secular space. Space becomes a symbol of itself. The world of the spirit becomes visible by purposeful abstraction and disembodiment. In the Eastern Orthodox church, sculpture largely disappears, in order to avoid the daemons which inhabit pagan statues.

Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

At the same time in the West, religious art burgeons with the corporeal, as the very physical bodies inhabit an engorged space. Both figures and architecture bulge from the plane, inviting a participatory sensuality of looking. It is hard to keep from ballooning your cheeks when looking at a Madonna by Piero della Francesca, as in his “Brera Altarpiece.”

The Problem with Graven Images.

Although the god of Genesis is the first image-maker, in Exodus, and in Deuteronomy, we are given the starkest injunctions against following suit:

You shall have no other gods beside Me. You shall make you no carved likeness and no image of what is in the heavens above or what is on the earth below or what is in the waters beneath the earth. You shall not bow to them and you shall not worship them, for I am the Lord your God, a jealous god… Exodus 20:1-5 (Robert Alter translation)

Is this a blanket prohibition against image making? Or does it just prohibit making images of other deities, such as gods of the heavens, gods of earth, gods of the waters, gods of the lower regions? As Alter points out, these different regions were each ruled by a different god in the ancient Canaanite mythologies. In any case, it seems to presuppose that we will make images of these other gods, anyway, but then we must not worship them.

What about praying to an icon? Is it worship? Is it worshipping the picture itself? Or the saint depicted there? Or the deity witnessed by the saint? Is the icon a representation, or is it, as Florensky says, the actual saint?

In the Eastern Orthodox Church and among Catholics and some others, the devotion one gives to icons is called veneration. The definitions of veneration vary among different churches, but always contain distinctions that attempt to separate it from idol worship.

I have Orthodox friends who tell me that in museums, when no one is looking, they kiss the icons. “This is what we do,” is their explanation.

In the 8th and 9th centuries the long disputes about the possible heretical nature of icons turned murderous. So many holy paintings were smashed or thrown into the sea that few images remain from the first millennium. Finally in 787 the Seventh Ecumenical Council proclaimed that it was now a heresy to forbid icons, because that would seem to deny that Christ was god made human. (An earlier Ecumenical Council, also called the “Seventh,” had ruled exactly the opposite. These things get very complicated for the outsider.)

Andrei Rublev.

Andre Rublev with Scenes from His Life.

Museum of Russian Icons

One of the great surprises in the Museum of Russian Icons is the painting showing Andrei Rublev, Russia’s most revered icon painter. He stands in the center, holding an icon while around him are scenes from his life. At first I assumed that the icon he was holding would just be a smaller image of the icon I was looking at, leading to a mise en abyme, but looking closer I saw that it was his most revered work, “The Trinity.” The format of a central figure framed by smaller icons is often used to show a saint and his life, and I was shocked to find it used for an artist, until I read in the label that Rublev was canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988.

After the fall of Byzantium and Rome, the Russian church fathers called Moscow “the Third Rome.” They said that the tsardom of Holy Russia made visible the heavenly kingdom of Christ on earth and that the ubiquity of icons–in churches, in households of aristocrats and peasants–showed that Russia was under divine protection. Given the importance of icons and their function as scripture, for the illiterate, and as a vehicle for union with god, for the adept,–this canonization makes perfect sense.

The techniques of icon painting have stayed remarkably constant over the centuries. Except for the brilliance of its colors, and the striking chartreuse sky, the icon showing Andrei Rublev, painted in 2003, feels as old as many of the works surrounding it.

And yes, Tarkovsky’s movie of the same name, violent and cruel and immensely beautiful, is a must. It is an icon.

Icon Painting Technique.

The technique for making icons is time consuming, painstaking, conserved and conservative. A step-by-step contemporary manual can be found online, but I will summarize Florensky’s briefer outline of the process:

A board is dried, then carved in the center, to leave a raised margin on all sides.

The back is reinforced to prevent warping. Linen cloth is glued to the front.

This is covered by a coat of whitewash, and seven coats of gesso, with each coat being polished with pumice after it dries.

Now the pattern of the icon is engraved in the superbly smooth surface.

The “painting” of the icon begins and ends with gold.

The first gold appears in the haloes, sometimes also the whole background, sometimes the sky or other places. Florensky says that this gold leafing of the light is what incarnates the icon. The icon is executed upon light.

Museum of Russian Icons

Here a sky of gold leaf separates the heavens from the earth in this icon of the life of the prophet Elijah. In the center, a raven brings food; at lower left an angel offers bread and announces Elijah’s trip to the mountain; at the top, in a fiery whirlwind protected by an angel, a chariot of fire drawn by four horses takes the Prophet to heaven while he is still alive; at the upper right, he throws down his cloak to his disciple Elisha.

To continue with the process of painting:

After the first gold come the colors, which are the visual images of the ideas.

The clothing and backgrounds are painted first, followed by hands and feet.

Finally the face, which expresses the inner life.

The last gold to be applied forms the fine highlights on the folds of clothing.

The gold and the paint, Florensky says, belong to different spheres, the gold representing the abstract and divine, the paint showing the material and created. While the broad areas of gold leaf represent the pure light of Creation, the fine lines of gold highlights on garments or flames are there to make part of the invisible realm comprehensible: they are lines of divine energy constituting the force field of the icon.

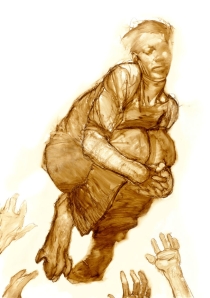

Museum of Russian Icons

Saint John of the Ladder was a 7th Century monk at the monastery on Mount Sinai; his book, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, gives instructions on ascending to heaven by means of ascetism. The icons representing this ascent show the ladder reaching from earth to heaven, with a group of monks at the bottom; a few ascend, helped by angels, while others, beset by demons, fall into the flames of the mouth of hell, where Satan waits.

Of course, the use of gold leaf goes way back, and we see it in the Greco-Egyptian burial portraits as in this one of a young man. But here it is an indication of material wealth and worldly standing and has little to do with the spiritual world.

Aegyptisches Museum, Berlin.

Courtesy Wikipedia.

The Missing Specks.

Having spent a large part of my youth looking through microscopes, I am doomed to find the tiniest specks of great importance. A while back I became obsessed with the hinges on the smashed doors of Hell in a fresco by Fra Angelico. But now, with these icons, I am fascinated by the absence of specks. Or rather eye-highlights, those tiny white dots in the pupils, reflecting an external light source. Such eye sparks have been used since ancient times by painters to enliven and individualize their portraits. Doxiadis, in her excellent book on the Fayum paintings, notes that while the Greco-Eyptian portraits often have eye-highlights, the Byzantine icons never have them.

If, while you wander around the Russian Icon Museum, you concentrate on the eyes of the saints, you will see this absence of highlights. It’s not that the holy figures look dead exactly, but rather that they don’t look lively. They don’t seem to partake of our sort of life. This can make them have a seriousness that sometimes feels bewildering.

If, while you wander around the Russian Icon Museum, you concentrate on the eyes of the saints, you will see this absence of highlights. It’s not that the holy figures look dead exactly, but rather that they don’t look lively. They don’t seem to partake of our sort of life. This can make them have a seriousness that sometimes feels bewildering.

Instead of these specks, in the icons the whites of the eyes are often the whitest part of the painting; the eyes seem to glow from within, as though for saints, the true illumination is inside.

Why do they all look like that?

My friend said one day at lunch, Oh, icons, don’t they all look the same? Why do they all look like that?

It’s partly true: many icons resemble each other very closely, clearly copies of some one original. Perhaps it’s like repeating a prayer, or a hymn, or a devotional song to Krishna: when you find one that captures the soul, you repeat it.

According to Florensky, when an icon is the first representation of an authentic religious vision in such a way that it reveals that vision to others, it becomes a “first-appeared” or prototype. When other painters copy this “first-appeared” icon, the spiritual content is identical, even if the form is varied or changed a little––as long as the icon painter of the copy is able to deeply inhabit that first painter’s vision.

Consider the account of an explorer who first describes newly discovered territory, says Florensky. Influenced by that description, a later traveler comes to that place, and writes his own report. While the first explorer has historical priority, the later one may write a better account. They are still accounts of the same location. So, too, the icons represent the same vision, but the later copy may in fact be better than the prototype.

Or perhaps one can think of the subsequent copies of some original “first-appeared” icon like the interpretations by different musicians of the same classical piece. And sometimes the variations will be more strident departures, with variations and improvisations following only the slimmest backbone of the prototype.

Florensky says that icon painters are halfway between priests and laypeople, and should lead semi-monastic lives––practicing humility, purity, piety under threat of eternal damnation. But I suspect they are humans, artists, flawed with passions. I suspect these rules of icons, like all rules, will be broken.

Showing the Human and the Divine.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai.

Courtesy Wikipedia

Let’s go back to one of the earliest icons still in existence, the 6th century Christ Pantocrator in Saint Catherine’s Monastery, Mount Sinai. Unlike most later icons, this one is done in encaustic on a wooden panel. There’s something else odd here. If the subject were human, we might think he had a broken nose or a wandering eye.

Some think that one side of the face is so different from the other in order to represent the dual nature of Christ, completely god and completely human, yet in no way a mixture of the two into a single nature, which would, in fact, be heresy.

I know we humans are not symmetrical, nor are our faces. But the two sides of the face in this image are so strikingly different that I made two digital composites, one of the left side, one of the right, to try to see if one really seemed more human, the other more divine. I leave it to you to tell me what you think.

The Veil Pulled Away.

The icon painter has not created the images, says Florensky–going into a miraculous negation of a negation–rather the images have simply appeared within our contemplation, and the painter has parted the veil, taking away the obstacle to our seeing. The saint appears to the painter and is found by the painter, but never invented by him, even in his wildest imagination.

Florensky also says that the saints are the only real icon painters, for it is they who direct the hands of the painters. Of course, the earthly painters must have the correct preparation: they must be technically skilled enough to be able to depict the sacred vision, and be spiritually adept enough to respond to saintly instruction.

Are the saints acting here like the ancient muses? Companions of the Olympian gods, they too acted to bring down divine inspiration to the human artist. Although the resulting work was not usually a portrait of that same muse.

The Work of Art vs. the Icon.

For Florensky, an icon is not a work of art but of revelation. It is always “either more than itself, in becoming for us an image of a heavenly vision, or less than itself, in failing to open our consciousness to the world beyond our senses–then it is merely a board with some paint on it.”

Thus for him, there is no stage in between, where the icon is simply an example of ancient fine art. Fine art, he says, has no power intrinsic to itself, but only when it evokes in us “the reality of the other world (as the pungent scent of seaweed in the air evokes in us the still faraway ocean).” For him it is a grave danger to think of the icon while separating it from the saint.

For us, though, especially us non-believers, if the icons open up the other world, but it is a different other world from the one intended by the icon painter, are we getting at something behind or deeper or more primordial than the product of a particular sect? Or are we simply falling into damnable error? And with secular fine art–if it, too, evokes some other reality of a world beyond the senses, isn’t it getting somewhere?

Windows to the Other World.

One of the things I find most interesting about Florensky’s Iconostasis is his notion of windows. The iconostasis of the title is a wall separating the altar from the worshippers in Eastern Orthodox churches; the wall is covered with icons, which act, Florensky says, as windows. Destroy the iconostasis and it would be like erecting an impenetrable wall. To destroy an icon is like blocking a window, smearing the glass, weakening the light of the spirit. He goes on to say about windows:

Thus a window is a window because a region of light opens out beyond it; hence, the window giving us this light is not itself “like” the light, nor is it subjectively linked in our imagination with our ideas of light, but the window is that very light itself(….) But the window (…)beyond its function as carrier of light – is no longer a window but dead wood and mere glass.

And just as a window separated from its function is just a construction of wood and glass, so an icon considered as art rather than miracle is just daubs of paint on a board.

But for the ancient ascetics at the height of their devotions, Florensky adds, icons weren’t only windows to the other world; they also became doorways through which the saints could descend into this one. This notion of passing between worlds lies at the heart of my recent work.

Fayum. c. 98-117 Courtesy of the

Trustees of the British Museum

In a few cases the Fayum portraits are still intact in their mummy wrappings. The effect is uncanny, for suddenly the portraits look like faces peering at us through a window from the world of the dead. The notion of the icon as window into the spirit world seems to go all the way back to the origins of the icon.

Fayum. c. 98-117 AD Courtesy

of the Trustees of the British Museum

Looking at the Sacred Art of Others.

c. 1880 Museum of Russian Icons

What are we doing when we look at the sacred works of others? One shouldn’t gloss over this puzzlement, I think.

If the icon is both a window into the mystical experience of the painter and a door allowing the saint to come into the believer’s world, am I, unbeliever that I am, hoping to stand in the line of sight, to see what I can intercept of this uncanny conversation? Am I trying to pluck some illuminating beam from a game of catch and mirrors with the gods? Or is this how I try to school myself in ways of representing transcendence.

What accounts for the transcendence, when it comes? Is it a trick of the brain? the technique of the artist? the power of the narrative? the spiritual preparation of the viewer? the force of the saint? The atheist, the neuroscientist, the art critic, the narratologist, the priest, and the mystic each have different explanations.

But simply as a museum-goer what I wonder is: If both religious and secular art lead to the sublime, are the paths different? And the ends? Does it have to do with where one places the light?

This is what keeps me going back. Some mysteries I persist in rubbing up against, even if, or because, I have no hope of understanding them. Anyone who has been in a museum after hours knows the odd susurrus of the galleries in the dark.

***

This essay was first published on April 10, 2012 on The Arts Fuse as “Gods in the Gallery: A Visit to the Museum of Russian Icons”